Who are we, or what are we? What do we do—the rest of us—in the age of systems? And, is it possible to live differently? With some help from Illich, yes.

- The »person« is something loosely embedded in a hierarchy of self-organizing systems; we are things, like other things, that have inputs and outputs all of which, in one way or another, are all accountable as »information«.

- Don’t try to do anything. Monitor everything. Worry. (Turn worry into distraction and entertainment.) Manage if you can.

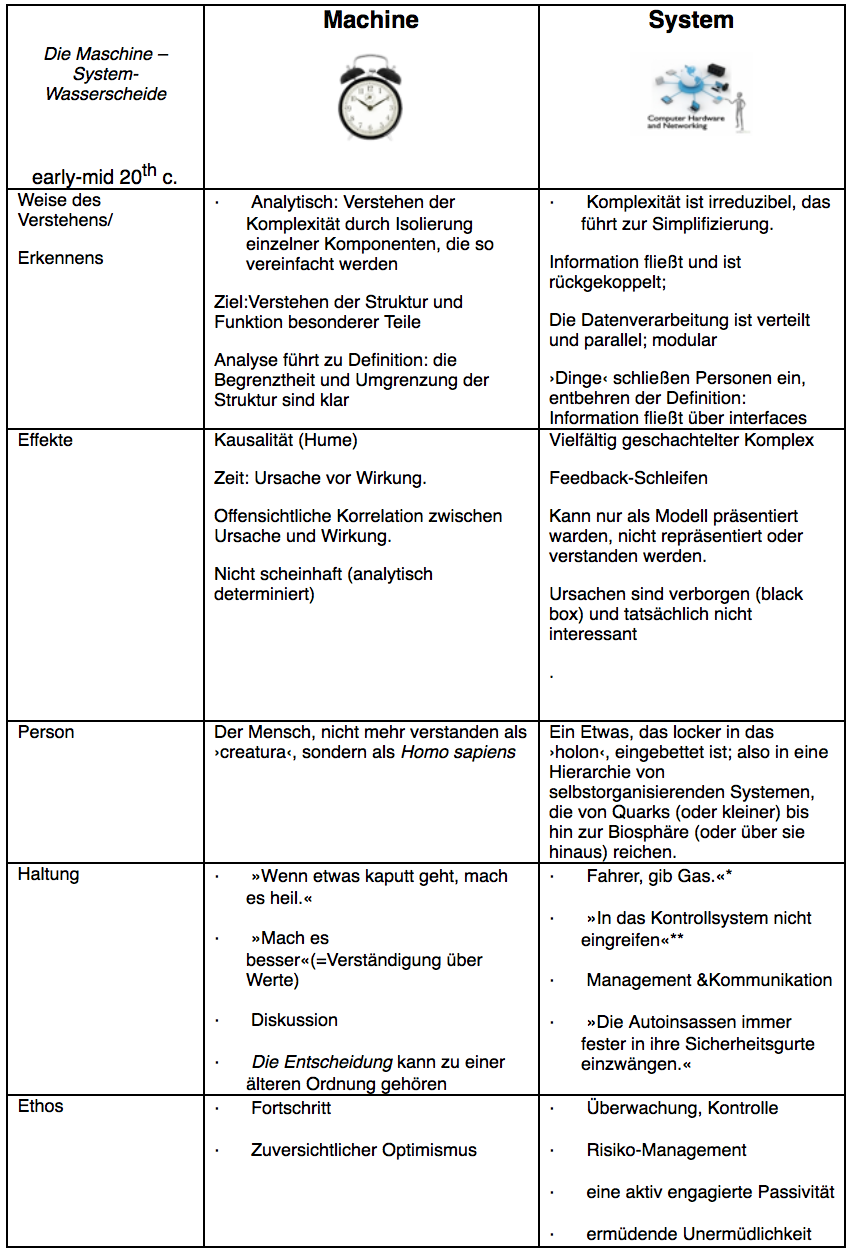

See »Machine-System Watershed,« an epistemic shift that occurs in the first half of the 20th century.

Effects of this shift on »The Rest of Us« in the Age of Systems

- Worry, distraction, entertainment: We are told that no matter how we feel or what we think we are in a state of constant risk, perpetual crisis. Like in the texting cartoon, data must be monitored, messages received and sent, information forced to flow. This is always distracting, often worrying, sometimes disabling, but it can occasionally be turned into a perverse kind of entertainment (e.g., monitoring your bad health through your »watch« [which is now definitely not a »clock«]).

- We are distracted, and we seem to want to be distracted.

- No time: Overwhelmed: »How are you?« »Crazy busy!« No one is »Fine« now.

- People avoid introspection: 6-15 minutes alone with one’s thoughts is »unpleasant.«

- People will shock themselves if left alone with their thoughts (65% of men; 15% or women; people who said they would do anything to avoid a painful shock).

- Even when we have paid time off, we don’t take it. (Average vacation days Americans have after 25 yrs on a job: 15.7. Only Japanese are worse. 57% of American workers had unused vacation time at end of year. On average workers take only 60% of paid vacation time.)

- No thought or reflection:

- There is a widespread belief that thinking and feeling will slow you down.

- Passion by proxy: You tell people your positions on matters of public discussion by sending them to some »expert« who represents your view best. No face-to-face discussion where you have the chance to see and feel the effects of your thought and where you have a chance to empathize with the other.

- No time to construct a narrative account of your life. Especially no chance to construct the narrative that links »private troubles« to »public issues,« the link between history and biography that C. Wright Mills said activates the »sociological imagination« that allows individuals and groups the chance to imagine creative responses to our social situation.

- No movement: »Crisis understood as a call for acceleration … also justifies the depredation of space, time and resources for the sake of motorized wheels and it does so to the detriment of people who want to use their feet.« Many people cannot move. Using your feet is risky (cartoon).

- No touch: Culture of simulation and spectacle in which image becomes reality. People seek digital mediation of meeting and mating.

- Her: Man falls in love with his computer’s operating system which calls herself »Samantha.«

- Doctors touch patients less. Even to take a pulse, they use a gadget.

- No »hand-to-hand« combat: Death happens on a screen (from a drone)

- Touch has been commoditized: People will go to a massage therapist instead of asking someone to rub his feet or help with a pain in the neck.

We have become senseless.

In the literature on the so-called neuro-biology of wisdom, there’s a story of some researchers trying to figure out how to operationalize »wisdom.« They posed »two roads diverged…« as a question just to see the kinds of answers it might evoke: How would you decide which path to take? Robert Frost famously took »the road less traveled by« and, he says, »that has made all the difference.« But the researchers were intrigued by the woman who said she would sit at the crossroad and talk to people coming down the path toward her. »I’d ask them all what lies in that direction. Eventually, I would decide which way to go.«

- She has time. (I’m not sure that it’s good to say, »She takes time.«)

- She reaches out to others whom she does not know and makes herself dependent, in a way, on them.

- She knows she is free.

- She decides.

That makes all the difference.

* »Driver, step on the gas.« Illich, The Right to Useful Unemployment 1977: »Krise das griechische Wort, das die ›Wahl‹ bezeichnete oder den ‘Wendepunkt’ bedeutet jetzt in allen modernen Sprachen: Gib Gas.Krise ruft jetzt die Vorstellung von einer bedenklichen, aber steuerbaren Bedrohung hervor, gegen die Geld, Manpower und Management ins Feld geführt werden können. Intensive Sorge um die Sterbenden, bürokratische Vormundschft für die Opfer von Diskriminierung, Kernenergie für die Energiefresser sind typische Antworten.«

** »In das Kontrollsystem nicht eingreifen: Boeing 757 in 1983. Das Cockpit hatte nur zwei mechanische Instrumente. Alle Informationen wurden von Bildschirmen geliefert, die Bilder von Instrumenten zeigten. Sie waren Systeme in dem Sinn, dass sie so kompliziert waren, dass a) kein einzelner Mensch, nicht einmal eine kleine Gruppe, ihre Komplexität vollständig ergründen konnte und b) jeder konnte die 757 fliegen sogar ein Nichtpilot, günstige Umstände vorausgesetzt.

Ein Witz: Die Flugzeuge der Zukunft werden von einem Piloten und einem Hund geflogen warden. Der Pilot ist dazu da, den Hund zu füttern und der Hund soll den Piloten beißen, wenn der auch nur daran denkt, das Kontrollsystem zu berühren.